The Major League Baseball game played at Rickwood Field in June is just the latest in a long string of memories that make the nation’s oldest ballpark a treasured Birmingham icon.

By Bill Caton.

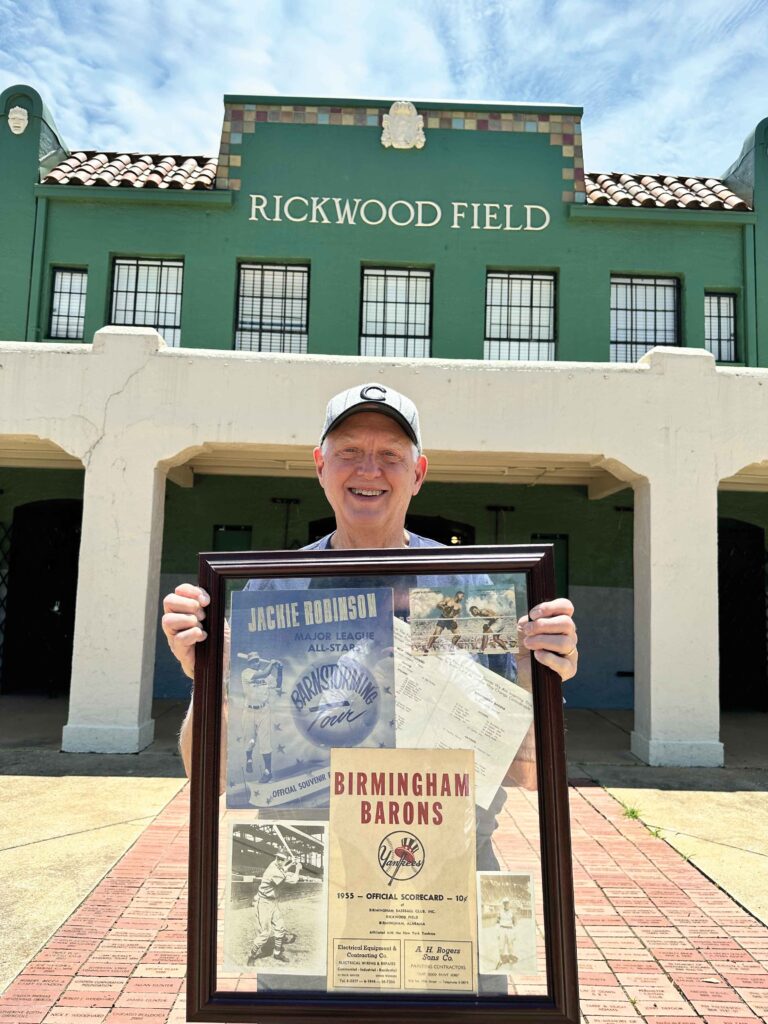

When Ken Damsgard was 11 years old he and his father traveled together from Decatur to Rickwood Field to watch the Birmingham Barons play an exhibition game against the New York Yankees. That was 1953 but it might as well have been happening in 2024 as Ken reminisced about the trip at lunch on a sunny afternoon in May.

He and his wife, Ann, had just taught the last Sunday school class of 5-year-olds for the year and the conversation turned to the summer and the official major league baseball game set to be played at Rickwood on June 20. As always, the present was shaped by memory.

“I got autographs from Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Eddie Lopat and Billy Hunter,” he said. “In 1955, Dad and I drove from Decatur to Rickwood to see Jackie Robinson’s All-Stars barnstorming tour. I got autographs from Jackie Robinson, Gil Hodges, Duke Snider, Luke Easter, Roy Campanella and Ralph Branca.”

“I don’t remember what we ate, but I imagine it was a hot dog,” Ken, now 82, said of his childhood trips to Rickwood. “Those are special memories of my Dad doing that with me.”

We think of the 114-year-old ballpark as if it is a relic of the past. But it is more than that; it lives in us in the present through the complexity of memory that provides context to our lives.

Great athletes have played there, from Babe Ruth to Dizzy Dean to Willie Mays to Reggie Jackson. The Negro Leagues flourished at Rickwood, but then in 1962 and 1963 there was no baseball played there because segregation laws prohibited blacks and whites from playing or watching baseball together. So it is fitting that MLB scheduled the first official major league game to celebrate the Negro Leagues and attempt to rekindle waning interest in the sport among the nation’s black citizens. The 5,000 available tickets for the game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants sold out in 40 minutes. An additional 3,300 tickets were to be given to members of the community.

“Our hope was to bring MLB to Birmingham to showcase America’s oldest ballpark,” said Gerald Watkins, chairman and executive director of Friends of Rickwood. “MLB gave us the motivation to raise money to fund major improvements. The city made a tremendous commitment of $5 million. Without them it wouldn’t have happened.”

Most of the money was spent getting the field fit for the major leaguers to play on. Excavation work started in October when construction crews dug up the old field to a depth of two feet, installed an MLB-quality drainage system and in May put down special grass called Tahoma 51, which is grown on a turf farm in Georgia and is used by high profile sports teams, said Watkins. The field was pampered by an MLB grounds crew. The grass will require a lot of maintenance going forward but Friends of Rickwood says it’s prepared for that.

Donations also paid for improvements to the dugouts and for locker rooms to be refurbished to be used as medical facilities for the game. Players will be using temporary modular buildings for locker rooms and club houses. They are plush facilities with video rooms, weight rooms and showers. Even the baseballs will receive special treatment, in their own humidors.

About 100 games a year are played at Rickwood. Miles College plays home games there, as do three of Birmingham’s high schools and a lot of travel teams. Friends of Rickwood is searching for a few more marquee events. Watkins said plans are for the Southwestern Athletic Conference tournament to be played there in 2025 or 2026. He also hopes to the have the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference tournament at Rickwood and to restart the Classic. They will certainly have a magnificent field to play on.

“The improvements on the field will allow us to attract more events and build status as a tourism spot,” Watkins said. “The (June 20) game will be a three-hour commercial for Birmingham. The publicity and people coming here are going to be very meaningful to (the city). There’ll be special events.

“The event is going to be pretty spectacular,” he said, “MLB is pulling out all the stops. We will have a fan plaza on the lot next door. There will be souvenirs, food and beverages. It will have television screens showing the game and will be adorned with pennants and signs describing in detail the heroes of the Negro Leagues.”

Baseball Hall of Famer Willie Mays was invited to attend and special preparations were made for him, but he died two days before the event. His passing brought to mind a special memory that shapes my present. Only 12 years after Ken’s last trip to segregated Rickwood with his father, I went to the library at Edgewood Elementary School in Homewood where I was a fifth grader, and checked out a biography of Willie Mays, a black baseball player in the integrated MLB from Alabama and one of my sports heroes.

And so my experience at Rickwood was different than Ken’s, but my visits to the old park are another addition to our collective memory. My father died in 2006 but he remains with me when I remember sitting with him in the steamy Birmingham night to watch Reggie Jackson, Rollie Fingers, Vida Blue, Tony Larussa and others as clouds of tobacco smoke and bugs swirled around the lights. I don’t remember what we talked about; I only remember him sitting with me in 1967 as both blacks and whites were together in the stands and on the field.