by Sherrel Wheeler Stewart

In my house, we often were reminded, “Do not speed. If the police stop you, keep your hands on the steering wheel. Answer any question with ‘yes, sir’ and ‘no, sir.’ “Those words were from my father, a preacher who just wanted his kids to make it home safely every day.

Mrs. Mary B. Woodruff was my fifth-grade teacher at Riley Elementary School. She taught art, but she also was determined to teach black literature, history and culture to every student who entered her door or crossed her path.

The fact that much of what this teacher taught us about black history and culture was not included in our state-approved textbooks didn’t matter. Mrs. Woodruff, a stern woman, insisted that every student learn that poem and many others from Harlem Renaissance writers.

Every day, there were at least 30 of us seated in desks with wooden seats and metal sides. The rows were neat. You couldn’t chew gum or eat candy in class. Our skin tones varied, but in many ways, we were all the same, and so were most of our teachers – black in Birmingham.

One after the other, we marched to the front of the room to recite the poem, after days or learning it line by line.

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

When my turn came, I rushed through my recitation, but Mrs. Woodruff made me repeat it. She wanted me to slow it down.

I had no idea what it meant to sing America – other than our morning ritual that included the Star-Spangled Banner or America the Beautiful and the Pledge of Allegiance.

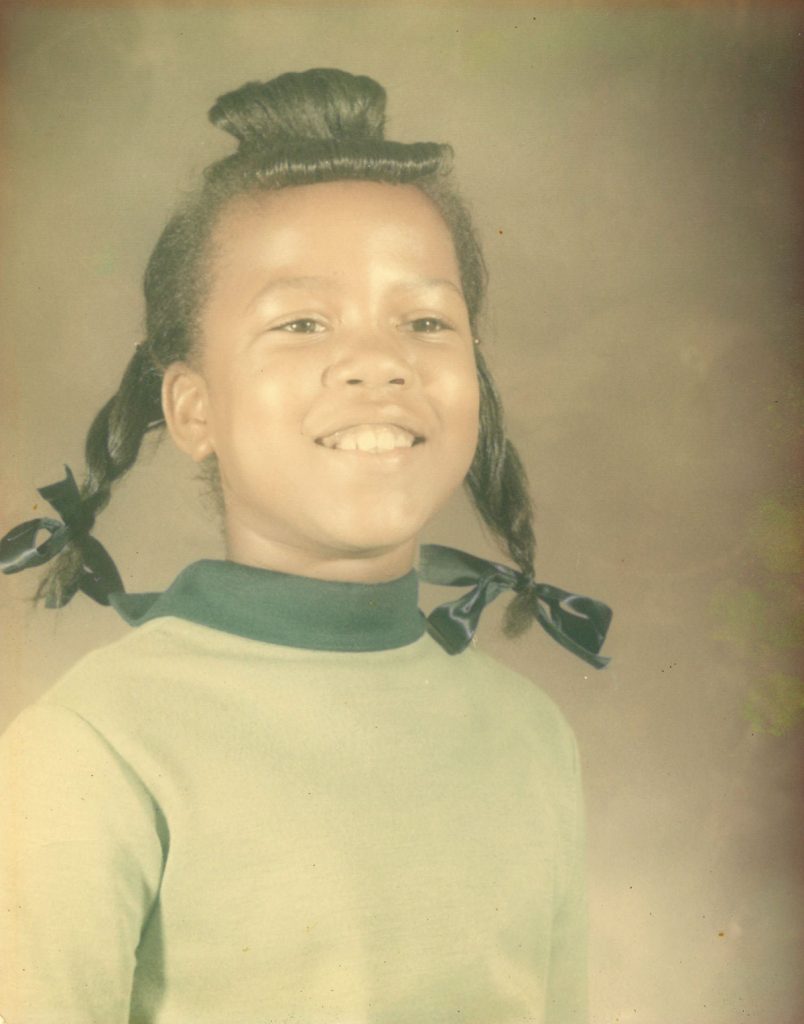

I had questions for Mrs. Woodruff like: Is this talking about me? The teacher tried to explain the poem to me and a whole room full of 10 year olds. “Wheeler, one day, you will understand,” she said.

For me, that day has come – about 50 years later. It has come for others, too.

George Floyd, dead. His life choked away on a city street while the world watched.

He repeatedly said: “I, can’t breathe,” because a police officer’s knee was on his neck. Floyd could not escape.

Protesters responded with anger and angst in Birmingham and around the world. It appeared that the life of this black man had no value, in the eyes of some.

It’s a picture that has played out here, too – foot on the neck, that is.

They send me to eat in the kitchen when company comes.

My deceased friend Wash Booker told me about growing up in Loveman Village, a former public housing community in Titusville. In the days when police commissioner Bull Conner reigned, police officers played cruel tricks on Black boys, starting at an early age showing them disrespect. The officers would call the boys over to the car and tell them to stick their head inside the window. They would roll the window up and trap the children’s necks, my friend said.

Years later, Birmingham erupted in racial unrest after an innocent and unarmed teen–aged girl, Bonita Carter was killed by a police officer in 1978. The officer said he thought Carter was involved in a robbery attempt at a convenience store in Kingston.

In 1979, Birmingham elected its first Black mayor. Richard Arrington promised to change the culture of the police department, but he had to take on institutions that had been in place for years.

At the same time, there was a culture of policing in communities outside of the city limits. Unwritten codes – especially for boys in the ’60s, ’70s and early ’80s – quietly governed how they traveled about. Don’t run the stop sign in Lipscomb. Don’t even go near the speed limit in north Jefferson County around Kimberly and Morris. And Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, Hoover and over the mountain areas are all off limits, unless you are going to work.

In my house, we often were reminded, “Do not speed. If the police stop you, keep your hands on the steering wheel. Answer any question with ‘yes, sir’ and ‘no, sir.’ “Those words were from my father, a preacher who just wanted his kids to make it home safely every day.

Talk with black people who have lived in this community for years, and they will tell you about the changes they have seen.

But they will also remind you about the questions they have had in the not so distant past. Like in 2014 when Aubrey Williams was shot by a Birmingham police officer while his hands and knees were on the ground. Or on Thanksgiving 2018 when E.J. Bradford was killed by a policeman in Hoover.

Williams was not charged in the holdup that originally led to the police altercation. The police officer who shot Bradford was exonerated. Bradford’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit in federal court.

Beyond the direct conflicts between police and citizens, there exists in metro Birmingham and similar places throughout the nation, a deep divide. This divide is not so simple as black and blue vs. black and brown.

Federal courts mandated desegregation in schools, housing, public transit, and other institutions years ago. But whether those laws bring true integration and acceptance, remains an unanswered question, decades after Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth defied Bull Conner, after we sat on the front seat of the bus.

In this place where four little black girls were killed by a bomb blast in a church on September Sunday morning, and two boys slain that same day because of their skin color in 1963, the total community has not fully reckoned with race.

Beyond the skin color, are we really different? What does it matter? And who cares?

Why am I sent to the kitchen when company comes? Don’t you know all our lives have value?

Until that day in Minneapolis when George Floyd took his last breathe as officer Derek Chauvin planted his knee on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, a majority of non-black Birmingham metro residents probably thought they could answer those questions with confidence.

We are at the table. Before COVID19 set in, you could walk into almost any local restaurant – whether it’s Eagles by the railroad tracks in Acipco-Finley, or Another Broken Egg in Mountain Brook – and see Black people eating with their families or white friends or Asian people laughing with a mixed group.

Everything seems fine through that OK lens. The table looks complete.

Then there’s reality.

Have the unwritten codes been abolished?

Are our communities still divided by race and class? We know the answers, but we don’t know why.

Recently I saw large diverse crowds gathered in parks across the city, peacefully calling for change.

I saw little black, brown, and white children playing together in a Homewood Park.

I saw a white man carrying a black toddler close to his chest in a Trussville grocery store. And I watched as he gingerly placed her into a car seat and fastened her in.

There are challenges. As a community, we have so far to go.

Why are municipal court rooms often filled with Black people and brown people, struggling to pay fines for minor offenses?

Why are there so few grocery stores and other retail shops in the inner city, forcing you to go into other communities where you may not be recognized as valuable or important?

Where is that long-awaited tomorrow?

I, too, am America.